SNCC 50th Anniversary Conference

April 15-18, 2010

Raleigh, NC

Press

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=126045761

SNCC folk,

What a wonderful five days at Shaw in Raleigh to celebrate the history of SNCC, to re-establish old connections and make new ones, all in the service of the continuing struggle for justice. As a historian and "outsider" to the SNCC family, it was truly my honor to be a part of this historic gathering, to see some of you again, meet many of you for the first time, and to document aspects of the festivities with my camera. It is always impressive to me the way SNCC vets graciously tolerate, and often lovingly embrace, those of us hanging around the edges of your world - the scholars, the students, the activists, admirers and friends of SNCC. We are all "children of SNCC" and each of us has a personal story about the way your history and legacy has transformed our lives. Thank you.

I have posted 352 photographs from the conference to a website: http://sncc50thanniversaryconference.shutterfly.com/

This is by no means a comprehensive record of

events, but rather glimpses of my experience there. Please feel free

to head on over and take a look. Please also consider adding your

own photos to the website, as well as a comment in the Guestbook to

let me know what your impressions are. I also posted about a dozen

excellent links to online resources related to SNCC's history.

Please feel free to

share the link to this website with anyone else in your network that

you think might enjoy taking a look at the photos or links. In

addition, if you would like me to send you the original digital file

of any of my photos, I am happy to do so. Just drop me an email with

the image number(s).

Again, thank you for your individual and

collective contributions to the transformation of our society into a

more democratic and just place! I took to heart what Mr. Belafonte

said when he challenged us to more vigorously engage the struggle in

our current historical moment, but I was also deeply moved by Ms.

Reagon's poetic reminder at the closing session that while there is

great work yet to be done, that it is ok to pause and acknowledge,

even lift up, the epic contributions you all made to a different

moment in time. We don't want to get lost in nostalgia, but it is

ok, and even good and right, that you and we pause to reflect on

what has gone before, to take stock, learn some lessons and seek to

draw out whatever insight

and guidance this history might offer us as we continue to struggle

against the various injustices of the early 21st century...

Thanks again for letting this skinny white dude from Cleveland, Ohio, enter your "circle of trust"... it has made all the difference to me.

Enjoy the photos!

a lutta continua,

Patrick

The Tribe of SNCC

by TOM HAYDEN

April 20, 2010Raleigh, North Carolina

One thousand enthusiastic celebrants at the fiftieth anniversary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee here were credited by a top White House official with making possible the Barack Obama presidency, as the group passed the torch to a new generation fighting for a constitutional right to quality education.

It may have been the last assemblage of the original SNCC tribe of organizers, now averaging 65 years in age, but the promise of SNCC's children, now between their teens and 30s, was evident in hundreds of young faces from all over the country.

US Attorney General Eric Holder spoke on Saturday at the same Raleigh site where SNCC was founded as a coordinating network for the exploding sit-in movement that began in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960. After internal debate, the conference steering committee invited President Obama. The decision to send Holder was freighted with memories of Justice Department officials in the early 1960s who, after initial hesitancy, often struggled alone to prevent segregationist violence against young civil rights workers helping local people to register and vote. John Doar, now 89, who faced down racist officials on many occasions, sat in the crowd as the new attorney general spoke.

Holder, under fire from the right as he tries to rebuild the Justice Department's civil rights division, told the crowd that "the nation is in your debt."

"There is a straight line from those lunch counter sit-ins [of 1960] to the Oval Office today, and a straight line to the sixth floor of the Justice Department where I serve today," Holder said. His late sister-in-law, Vivian Malone Jones, defied Governor George Wallace to integrate the University of Alabama in 1963.

"This progress could not have happened without SNCC's work," he went on. "The path was blazed by you, and I stand on your shoulders."

Holder pledged to strengthen civil rights enforcement and place a new emphasis on trying to reverse policies that have incarcerated young men and women of color for longer sentences than their white counterparts.

"We are counting on you to rekindle the spirit of 1960 and build on SNCC's achievements. You look strong to me. This army is not disbanding. There still is marching to be done. Stay as committed as back then."

Holder's speech attracted little attention in the mainstream media. But if a primary purpose of the SNCC conference was to claim a legacy in history, the legitimizing import of Holder's official remarks was important. In the early 1960s, SNCC was criticized privately by President John Kennedy, prior to the 1963 March on Washington, as a group of "radicals" and "sons of bitches." Representative John Lewis, who preceded Holder on the Raleigh stage, was under severe pressure in 1963 from the Kennedy administration and mainstream civil rights leaders to tone down the speech, in which he famously demanded to know, "Where is our political party?" Robert Kennedy at first tried to freeze the Freedom Rides, and even questioned the loyalty of the early SNCC militants. In time, that tension would lessen, as SNCC kept up the heat on the Kennedys, a process that may lie ahead in SNCC's relations with Barack Obama.

SNCC became "a blip in the dominant [civil rights] narrative," according to 37-year-old Tufts historian Peniel Joseph, who attended the conference. Historicizing SNCC is extremely important, he said, though there is a danger that "glorifying" the early SNCC implies that a "bad SNCC" developed after 1966 with the rise of Black Power, calls for self-defense and revolutionary internationalism. Those apparent extremes should not be discredited, Joseph said, but contextualized in the failed social response of the US government; the escalation of the Vietnam War at the same time as the Selma, Alabama, march; and the employment of counterintelligence programs by the FBI.

The historian Taylor Branch was one of the few to question whether SNCC inadvertently might have contributed to what he called the "shocking distortion of history" in which SNCC's role is largely erased. "The empirical achievements of the 1960s are buried under amnesia," Branch lamented. "It's understandable that segregationists would want to discredit that era. But we are complicit in failing to embrace nonviolence and our own achievements, partly because of the frustrations over how long it took for society to reform. As a result, many Americans don't know and appreciate the way the reforms we won have benefited them."

As an example, Branch pointed to the 1964 crisis at the Democratic National Convention, when the party establishment rejected the challenge of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic delegation, organized by SNCC. The compromise offered by Johnson--two seats without a vote--was indeed token, Branch said, but in a wider sense it was an effort that would lead to a more open Democratic Party. Completely forgotten, he claimed, is that at their convention a few weeks earlier, the Republicans expelled most of their few black delegates in order to win more white segregationist voters.

While the primary emphasis of the Raleigh conference was to celebrate SNCC's overall role in defeating segregation and winning voting rights, there was no effort at dividing "good" from "bad" SNCCs, to distance the organization from its more radical phases. The room was jammed with old militants of all stripes. Amiri Baraka gave a presentation on the black arts. Kathleen Cleaver, former wife of Eldridge Cleaver and now teaching at Emory University, stood cheering for third-graders from Oakland, California, where the Black Panther office was headquartered. Peniel Joseph is writing a positive history of the late Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Toure). (In private communications with Holder's office, the SNCC conference representatives lodged a forceful complaint against the transfer of another of their later chairs, H. Rap Brown [Jamil Abdullah al-Amin], to a high-security Colorado prison far from his Atlanta home. He is serving a life term for allegedly shooting two Atlanta sheriff's deputies in 2000 after they tried to arrest him at home for failure to appear on a speeding offense. One of the deputies died.)

The fact that the Raleigh conference was overwhelmingly interracial was a sign that old antagonisms have been transcended and largely healed.

A women's workshop asserted a historic role for SNCC in the rise of the women's liberation movement, another once-contentious issue put to rest.

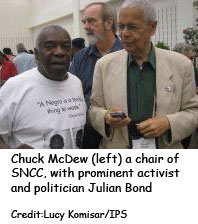

Dimmed the most in the legacy discussions was SNCC's early leadership in opposing the military draft and the Vietnam War. That opposition began as early as 1964, not in the later "bad" period, and resulted in SNCC original member Julian Bond's being expelled from the Georgia legislature in January 1966. A federal court restored Bond's seat, and he later became president of the national NAACP.

By comparison, the raging wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the latter now led by President Obama, were little mentioned during some forty-five workshops and forums. In fairness, it is safe to assume that the 1,000 participants were overwhelmingly critical of the current wars, and that point was driven home by keynote speakers like the Reverend James Lawson and Harry Belafonte. But the main focus of the workshops was SNCC's civil rights impact and legacy.

It will be impossible to report the outcome of so many workshops until transcripts are released by the organizers. The topics were diverse and speakers were many, including: the early student movement, how activists became field organizers, how SNCC built an organization, "more than a hamburger," Alabama/Black Power, Southwest Georgia, lessons of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and so on.

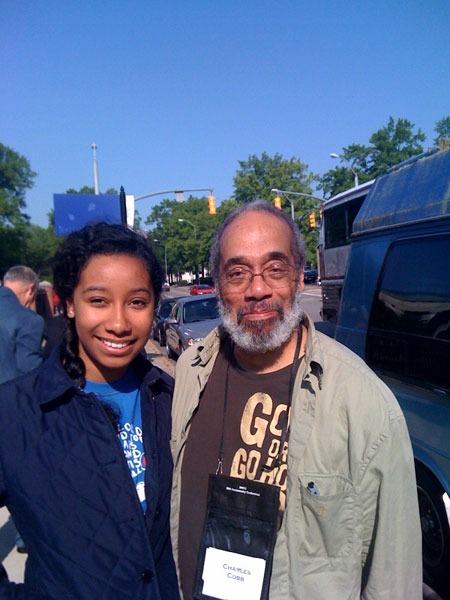

Perhaps the most important question on everyone's mind was the future. Just as important as securing a legacy in history was opening the way to a better tomorrow. That was the focus of two plenary sessions, which amounted to a ritual transition within the SNCC tribe. On Saturday in the sanctuary of the First Baptist Church, the grown-up "children" rose one by one to take their elders' places, with the quiet blessings of those elders who were still alive. While hundreds wept, clapped their hands and sang, they came to the pulpit to declare themselves: Maishe Moses (Bob and Janet Moses), her brother Omo, James Forman Jr. (James Forman and Dinky Romilly), Tarik Smith (Frank and Jean Smith), Sabina Varela (Maria Varela and Lorenzo Zuniga), Bakari Sellers (Cleveland and Gwendolyn Sellers), Zora Cobb (Charles Cobb and Ann Chin), Hollis Watkins Jr. (Hollis Watkins and Nayo Barbara Watkins), Gina Belafonte (Harry and Julie Belafonte). Sherry Bevel (James Bevel and Diane Nash) combined humor and compassion for her father, who was convicted of incest in 2008, released on appeal and died shortly afterward:

"It would be a shame if his wit and energy was forgotten. We have had great men and women who were caught up in drug or alcohol problems, or were philandering with underage girls. But I for one don't think we should just forget Thomas Jefferson."

The following morning, in SNCC style, the meaning of this ritual transition took material form. Bob Moses and David Dennis, who represented SNCC and CORE in Mississippi and still work together, addressed a large breakfast. In his customary low-key way, Moses asked people to "think about" pushing for a constitutional amendment to guarantee the right to quality education for every single American. People then sat in small discussion groups. The abstract idea was made real by the presence of young people, many of them the children of SNCC, who are already organizing through a remedial algebra project and a broader young people's project aimed against economic and educational disenfranchisement and mass incarceration of young people of color, their own generational peers. As the first SNCC stood with the demonized of the Black Belt, this newer generation was immersed in organizing the demonized of the inner cities. To discuss what such an effort might look like, sparked by two organizing efforts, the Algebra Project and the Young People's Project, aimed at addressing the educational and economic disenfranchisement of young people of color. Moses offered a few words of historical background:

"When Jimmie Travis was shot in 1963, we got into a Mississippi court. John Doar was there. The judge asked why are you taking illiterates to vote. So the subtext was education. In 1870 in Mississippi the Fifteenth Amendment had been approved. The black voters had put into the governors office Adelbert Ames, under the protection of federal troops. President Grant asked for an amendment to guarantee all children the right to an education. Then in 1876 the backlash came. They said the money should be used to build railroads in the Delta, not for schools. We got sharecropper education. That's where we were until 1963. Then we got Jim Crow out of public accommodations, out of the Democratic Party, and we got the right to vote. We didn't get Jim Crow out of education. So that's the work we have to do. Some people have issues with a Constitution written by white people. But think of it as an evolution. We have moved from being property to being second-class constitutional people, and now we must become constitutionalized as people with a right to quality education."

Moses asked the conference to repeat with him the preamble to the Constitution, beginning with the universally known phrase, "We, the People." He noted that it didn't say we the government, didn't even say we the citizens, an implied reference to immigrants of today. As I rolled the phrase around in my memory, I began to understand another way to say it, more in keeping with the SNCC tradition. If one takes the comma away, one can simply assert in common language, "Who are we? We the people," not something a politician wants to hear.

After Moses finished, Albert Sykes from Jackson, Mississippi, rose to represent the Young People's Project. Sykes first met Moses when he was in sixth grade in the Algebra Project, and gradually became a mentor and organizer, starting thirteen years ago. He called on the conference to unite behind his new generation. "We are transitioning from the sit-in movement of 1960 to a stand-up movement of young people. For us, literacy is the next frontier. And we're gonna need your moral capital, your financial capital, lawyers to get us out of jail, and we need to spread across the whole country."

As he spoke, at least 100 young people from many states were moving around the room distributing sign-up sheets. Moses said, "Now we're gonna ask you to do some work." The tables came alive with conversation.

Something had shifted in the long weekend. Now the past was very much present, and a future of some kind was beginning again. The tribe of SNCC was still gathered, their spirits high, but the children were leading now, and the work of the future was beginning again.

As one SNCC veteran, Doris Derby, declared as the conference wound down, "When they say SNCC is a state of mind, they are right."

About Tom Hayden

Tom Hayden, according to SNCC's original communications director, Julian Bond, was "the first person to write about SNCC," in 1960. Hayden teaches the sociology of social movements at Scripps College. His most recent book is The Long Sixties, From 1960 to Barack Obama (Paradigm). more...

Copyright © 2009 The Nation

Broadcast and print stories on SNCC 50th

Charlie Cobb curtain raiser

for Theroot.com

WUNC broadcast

with Charlie Cobb, Fran Beal and Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson

Florida Times-Union on Charlie Cobb

The tribe of SNCC by

Tom Hayden appearing in The Nation magazine

Charlotte Observer report on Holder

Julian on NPR

curtain raiser in News and Observer

Harry Belafonte in the News and Observer

NPR

another NPR story with Guyot photo

entire Eric Holder speech

Montgomery (AL) Advertiser on Bob Mants

CounterPunch

story

WALB in Albany,

Georgia

Gannett Washington Bureau story

http://www.theroot.com/views/women-sncc

How about running my IPS story on your media list. After all, I was

there 50 yrs ago.

Lucy Komisar

http://www.ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=51225

and

http://thekomisarscoop.com/2010/04/u-s-civil-rights-veterans-pass-torch-to-younger-generation/

Interview with Taylor Branch concerning SNCC's 50th Anniversary Conference.

The Student's Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) celebrated

its 50th reunion last weekend. SNCC played a major role in the

sit-ins, freedom rides, voter registration drives and marches that

defined the American Civil Rights movement.

Pulitzer-Prize winning historian Taylor Branch says SNCC's role in

shaping America is as essential as that of the Founding Fathers. He

reports from the conference:

interviewed by Susan Lehman

Susan Lehman: John Lewis, Julian Bond, Charles Cobb, Ruby Sales, Dave Dennis and other SNCC veterans gathered at Shaw University last weekend. What most surprised you about the 50th Anniversary conference?

Taylor Branch: What was most surprising was how many people showed up. SNCC people are notoriously argumentative. They are dying out. They are scattered all over the place. And yet, I don't know the precise number, but it seemed to me there were more than a thousand people there.

SL: How do you explain the big turnout?

TB: There is a hunger for what is fundamental. A lot of people think our national politics is out of whack. SNCC addressed problems that no one thought could be solved, and risked their lives doing it. They know they deserve credit for this. And I think they are alarmed about what is happening in the country. Apart from all this, there was probably a sense that for a lot of them, this is their last shot to get together with people they were bosom buddies with 50 years ago. If it's a 50th, and you miss it, you can't plausibly say, "Hmm, I'll skip this one and go to the 60th!

SL: How would you characterize

SNCC's legacy?

TB: SNCC played a far larger and

more positive role in American history than is commonly appreciated.

Correctly viewed -- and historically viewed -- the SNCC people

shoved into motion an awful lot of freedoms that changed the country

in fundamental ways we take for granted today. This extends far

beyond eliminating segregation. SNCC helped end -- literally -- the

spirit of terror in a whole region of the country where people were

afraid in a meeting room or a living room, or a downtown place that

had any mixed presence.

Doing so made people's hands sweat. Because violence was ever

present. People were getting beaten up, killed and insulted and

there was a lot of hatred running through the land. SNCC's witness

eliminated this and also changed the partisan structure of politics

in the whole country.

By winning the right to vote for black people, SNCC helped create

the two-party South. It also helped create - or stimulate -

prosperity in the South, which was impossible while the South was

gnarled up enforcing segregation. The region was not fit for

major-league sports teams, then, as soon as segregation was

eliminated, sports teams - the Atlanta Braves and Miami Dolphins

teams sprouted up, and the Sun Belt was born. There were all kinds

of blessings for lots of people. And not just black and white

people, but for women and the disabled. The women's movement and a

whole host of movements that followed came out of a fundamental

struggle over questions about what equal citizenship means, what the

role of politics is, and the responsibility of every student.

Properly viewed - and history will one day see it this way - the

Civil Rights movement in general, and SNCC people as the young shock

troops, playing the same role as the Founding Fathers did. They

confronted systems of hierarchy and oppression, and set into motion

a new politics of equal citizenship that benefited everybody.

On the uses of nonviolence

SL: What can be learned from SNCC's

successes in eliminating racial desegregation?

TB: The overwhelming lesson is that

they grounded themselves in nonviolence and in the notion that

people will respond to the moral values of equal citizenship and

democracy and basic religious morality, if it's dramatized

sufficiently. And they discovered a kind of nuclear energy in

nonviolent witness from the sit-ins to the voting rights era. That's

a pretty big discovery.

SL: Is there anything in

contemporary American political life that suggests nonviolence could

be as powerful a force now as it was during the Civil Rights

Movement?

TB: All political agitation is a

form of nonviolence and political debate will win out in the end.

But I don't see any contagious movements of nonviolence. One of my

biggest complaints when I got to universities is that no one is

studying nonviolence. Here you had a movement that came out from the

weakest and most invisible segment of society in civil rights; it

was a movement that adopted nonviolence and really shoved society --

against its own will -- in a direction of profound and beneficial

reform. Yet nonviolence isn't studied.

It's a travesty that you can go on university campuses in the

politics department and find people writing dissertations on minor

attack ads in a campaign but not studying something as sweeping as

the changes eight-year-old girls wrought on the national psyche by

walking in front of dogs and fire hoses. This is a pretty remarkable

thing. We are the oldest experimental democracy, and whole idea of

democracy is to settle disagreements by vote instead of the sword.

The vote -- as Dr. King used to say -- is an act of nonviolence.

It's not a to tally marginal issue.

SL: Speaking of voting and

marginalization -- If patterns of felony disenfranchisement persist,

we'll have a higher level of disenfranchisement among African

Americans in a few years, than we did at the time the Voting Rights

Act passed.

TB: This is a political issue that

needs to be addressed. Certainly the direction of American history

from the inception has been to widen the franchise, not to narrow

it. If we are actually narrowing it in a significant or politically

important way, that is a turn backwards in history and we should be

very skeptical and watchful about that.

SL: Attorney General Eric Holder

delivered the keynote address at the SNCC conference. What role did

government play in SNCC's understanding of the path to justice?

TB: This was an issue of tension

between SNCC and Dr. King. Dr. King always tried to knit together

the pressure from the movement withresults through politics. He was

always looking for way to outlaw segregation and secure voting

rights, legally. The legal part mattered. King tried to keep the

movement together, and, at the same time, he negotiated with all

three branches of government to move towards a voting rights law.

For King, the whole purpose of movement was to gain some footholds

in law. SNCC started that way, but was so disillusioned by the slow

performance of the federal government -- and the fact that the

federal government that had been so slow to move on Civil Rights was

that it was starting the war in Vietnam -- that they disregarded the

legal aspect. As an historical matter, I think this is why King

lasted longer. SNCC came apart when it scorned the delicate task of

keeping movement going and getting a political response.

SL: Was SNCC a racially-mixed

organization?

TB: It was almost entirely black

from 1960 - 1964. Those were important years. But then when they

made the enormously controversial and philosophically fraught

decision to bring 600 white college students down for freedom

summer, a lot of them stayed on, and to a large degree threatened to

swamp SNCC in inter-racialism. It was not smooth. Part of the inner

struggle of SNCC to this day was they professed to be above the race

issue, but in the crucible of risk and trying to work together

across unfamiliar cultures, there was a lot of friction. It was

controversial at this reunion to use the symbol of white and black

hands clasped, which was SNCC's original symbol. The symbol was

anachronistic. In the end, SNCC ended up being an all-black

organization. The reunion was about 90% black.

SL: You have written about the way

history and myth-making impede progress. Could you say a bit about

how this happens?

TB: Race is a powerful engine of

dangerous myth in American history. To some degree, it is today: a

lot of the Tea Party animus is undigested 1960's resentment that

people are called upon to act outside their comfort level with

people from different backgrounds and races, and that government is

forcing them to do this. And this is why they don't like the

government. And because it is subliminal and emotional, it's not

ever said directly. A fantasy is being fed to them: that if it

weren't for the government, they could be totally comfortable, would

be wealthy and not have problems. It has a lot of a success-church

mythology sprinkled with an awful lot of

federal-government-is-the-instrument-of-scary-minorities-and-foreigners,

and to that degree that kind of mythology. Some of those same people

are to tally blind to all the benefits - even to the white

southerners - that the Civil Rights movement brought to them.

The Future

SL: Harry Belafonte said, during the

speech he gave at the conference, that "no one should leave without

a passionate idea about what to do now." What ideas or issues

galvanized most passion?

TB: The issue of education and

non-functional schools, particularly in cities was a big issue. Bob

Moses, one of the most powerful forces in SNCC, has been working on

education issues for years. There was a lot of interest in prisons

and the burgeoning prison population. There are two million people

in jail; reasons for this has something do with sentencing

disparities of sentencing, and the effect of the drug war in

imprisoning people for nonviolent crime.

The two issues of prison and youth education dovetailed with some

people who were upset about fact that younger and younger kids,

particularly black kids, are incarcerated right out of school. A lot

of people were interested in peace issues and in the question of why

we are continually fighting wars, and, the question of whether there

is a correlation between our having government's tilt towards

increased executive power and the national security state, and the

fact that not only have we been involved in more long-standing wars,

but also that we are losing them.

When I saw Eric Holder, I felt badly that people like myself and

SNCC didn't applaud him and step up to offer support when he

announced plans to try 9/11 people in civilian courts. This was to

me, in a SNCC way that has to do with questions about what

fundamental democracy is, a courageous step. Essentially Holder was

saying: "We are not afraid to test our values in the open by putting

our case there and allowing defense to have its case, and that is

what the American system is about. And to fear that this might fail

or be dangerous is a step backward from our values and a surrender

to those who equate democracy with militarization."

SL: The Attorney General hasn't

officially retreated from his announced decision to try the 9/11

case in civilian court. So it's not too late to stand up and voice

support.

TB: You're right. I came out of the

Holder speech thinking that if SNCC wanted to write him a letter I'd

do what I could, and if anyone announced a march in support of that

decision, I will try to attend.

SL: After four days what do you

think was the ratio, amongst conference-goers, of hope to

hopelessness or just fatigue?

TB: I didn't sense a lot of

hopelessness. I sensed something more like determination and sprit.

There were a lot of people who said, "When we started SNCC, there

wasn't a lot of conscious talk about how that this was going to

change the South. The first thought was we couldn't put up with it

any more and that we simply wanted to do something that would show

we disagreed. And not necessarily because we predicted it would lead

to the kind of change it did." People started this because they

wanted to make a witness or because something welled up in them.

That's what a movement is. It wasn't calculated. Something

reminiscent of that spirit was present over the weekend.

SL: Last question: you used your

panel to talk about how SNCC doesn't take sufficient credit for the

profound changes it brought. What difference does it make if SNCC --

and its accomplishments -- are fully understood?

TB: SNCC doesn't claim the breadth

of its impact. And this hurts not only SNCC's own reputation, but

contemporary politics as well. It leaves a gap. People should be a

lot more optimistic about what you can achieve in politics than they

are today. The Pew organization just released a study that says a

huge percentage of people disparage government and say it is

worthless and you can't do anything about it. If everyone had a true

appreciation of breadth of changes spawned by the Civil Rights

movement in general -- and by SNCC in particular -- it would be hard

to justify that level of cynicism and opposition.

Taylor Branch is the author of, among many other books, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Parting the Waters.

"It seems to me that..."

Zora and Charlie Cobb

http://www.ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=51225

U.S. Civil Rights Veterans Pass Torch to Younger Generation

By Lucy Komisar*

RALEIGH, North Carolina, Apr 27, 2010 (IPS) - Robert Moses, 75, a

legendary leader and organiser in the 1960s U.S. civil rights

movement, was huddled with a dozen people discussing plans for a

campaign to make quality education a constitutional right. On one

side was his son Omowale, 38. On the other was John Doar, 89, head

of the civil rights division of the U.S. Justice Department in

1960-67 and prosecutor of the major civil rights cases of that era.

The age differences were noticeable at the conference they attended

this month in Raleigh, North Carolina, to commemorate the 50th

anniversary of the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating

Committee. It was a moment for the "elders" - as high school and

college students at the conference called them - to pass the torch

to a new generation of activists.

SNCC, or "snick", as it was known, was founded on the campus of a

black college, Shaw University in Raleigh, to coordinate the

Southern student civil rights movement. A few months earlier, four

black students had "sat-in" and demanded service at a lunch counter

at a Greensboro, NC Woolworth's department store that reserved

stools for whites. The management refused.

On succeeding days, more students joined them. As word spread, other

college students staged "sit-ins" around the South.

SNCC took the movement further, evolving from a coordinating

committee to an office that sent "field secretaries" to most

Southern states. By 1963, there were 181 young staff and volunteers

who lived and worked with local leaders to register and educate

black voters and wage economic campaigns to gain their rights.

The next year, 1,000 young people, mostly whites, came to

Mississippi for a SNCC campaign to register voters and run 28

political "freedom schools". Two of the whites and a Southern black

youth were murdered by racists.

In 1965, SNCC organised a Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

challenge to the all-white state delegation to the Democratic Party

Convention. In 1965, it challenged the seating of Mississippi's

congressional delegation in Washington. It supported black

candidates for Congress and local office; black elected officials in

the southern states increased from 72 in 1965 to 388 in 1968.

SNCC actions led to a ban on segregated Democratic Party

organisations and ultimately prompted Southern racists to quit and

join the Republican Party. The awareness SNCC created played a role

in Congressional passage of the anti-segregation Civil Rights Act of

1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

SNCC made foreign policy issues part of the black agenda. Staffer

Julian Bond won election to the Georgia legislature in 1965, but the

body refused to seat him because he endorsed SNCC's criticism of the

U.S. war in Vietnam. A year later, his admission was ordered by the

U.S. Supreme Court. He served for 20 years.

Bond told the conference that, "What began 50 years ago is not

history. It was a part of a mighty movement that started many years

ago and that continues to this day - ordinary women and men proving

they can perform extraordinary tasks in the pursuit of freedom."

That resonated with the young people. Abeni Nazer, 18, a freshman at

the University of Baltimore, said, "I've never met Dr. [Martin

Luther] King, I've never met Malcolm X [a Black Muslim leader

assassinated in 1965]. But Bob Moses and a lot of people here, I

actually get to meet them and I feel like, when you have first-hand

experience and you're sitting face to face with these people, it's

totally different than reading it in a book or seeing it on

television. It inspires me more; it puts the passion back."

Robert Moses is a bridge to the modern movement. A former high

school math teacher, in 1982, he started the Algebra Project, to

develop methods to teach math to low income and minority students.

That led to the Young People's Project, headed by his son Omowale,

which trains high school and college students to work with students

on math and to promote reform of math education. They follow SNCC's

strategy.

Albert Sykes, 26, a Jackson, Mississippi YPP leader told IPS that

SNCC's lesson was "start local and think local". He explained, "The

initial sit-in was four guys sitting at a lunch counter. It was a

single action but had a ripple effect. The message from the elders

is to stay local and do small incremental steps, which for YPP is

quality education as a constitutional right."

Later, addressing conference participants in Shaw's gymnasium, he

said, "We transition from Feb. 1, 1960 and the sit-in movement to

the 'stand up' movement. Young people in Jackson, Mississippi have

to stand up, young people from Chicago, Illinois, from Minnesota,

Georgia, have to stand up…" And the young people stood up to

applause from the "elders".

He complained that, "Some of the challenges come from the torch not

being property passed between the SNCC generation and our parents

and our parents' generation not handing the work to us."

Other SNCC leaders also seek to pass the torch. Ivanhoe Donaldson,

who organised for SNCC in Mississippi and Selma, Alabama and Bernard

Lafayette, who worked on a Selma voting rights campaign, joined

singer and civil rights supporter Harry Belafonte in 2005 to found

The Gathering for Justice.

Carmen Perez, 33, a worker for the group, said for her the challenge

was "a criminal justice system that incarcerates children".

Javier Maisonet, 25, who works in Chicago for YPP, said the sit-ins

put everything in perspective. He explained that one SNCC activist

said, "Once you come to terms with the worst thing that can happen

to you, you can do whatever needs to be done."

*Lucy Komisar attended the founding conference of SNCC in 1960. She

was editor of the Mississippi Free Press, a civil rights newspaper,

in 1962-63. Her website is

http://thekomisarscoop.com/.

Download SNCC

report by Mike Miller

SNCC at March on Washington--CNN

Sue Thrasher's blog on the SNCC reunion:

https://lcrm.lib.unc.edu/blog/index.php/2010/05/10/snccs-50th-thoughts-from-sue-thrasher/

Julian Bond’s talk:

http://monthlyreview.org/001001bond.php

Firsthand report from SNCC's Historic 50th Anniversary Gathering in Raleigh, NC, April 15-18. By Carl Davidson and other CCDS participants.