What Happened in Raleigh in 1960?

One of the most enthusiastic observers of the student protests in the early months of 1960 was Ella Baker, SCLC chief of staff. Baker hoped that a meeting of student leaders would enable protesters to communicate with each other and to acquire the knowledge necessary to sustain their movement. Her desire was that the student protest remain student led and not be taken over by an established civil rights organization.

By the second week of March 1960 Baker was working on plans for such a meeting to be held over Easter weekend, April 15-17 at her alma mater, Shaw University in Raleigh. After borrowing $800 from SCLC and contacting an acquaintance at Shaw to secure facilities there, she sent a note, signed by herself and Dr. King, to all major protest groups, asking them to send representatives to The Southwide Student Leadership Conference on Nonviolent Resistance to Segregation. In the letter, student leaders were offered the opportunity “TO SHARE experience gained in recent protest demonstrations and TO HELP chart future goals for effective action.” The purpose of the meeting was to achieve “a more unified sense of direction for training and action in Nonviolent Resistance.” The letter assured students that, although “Adult Freedom Fighters” would be present “for counsel and guidance,” the conference would be “youth centered.”

On March 16 Baker flew to Raleigh to finalize the arrangements. Since Shaw could only house about 40 people, Baker contacted nearby St. Augustine College, the YMCA, and local residents to arrange additional housing.

On April 5 Baker issued the first public announcement of the Shaw meeting. The release explained how student representatives from across the South had been invited, and that James Lawson, who had been expelled from Vanderbilt’s divinity school in March for advising the Nashville sit-in students to continue their protest, would be the keynote speaker.

On April 10 Dr. King spoke at Spelman College, and the next day talked with reporters about the upcoming Shaw conference. King predicted “a Southwide council of students will come out of the meeting,” one wrote. “He said he would serve in an advisory capacity only, and any future direction in the protest actions would come from the student themselves.” He also urged the students to learn more about the philosophy of nonviolence.

Nearly 100 of the student demonstration leaders from 19 states spent the first weekend in April at Highlander Folk School in New Market, Tennessee at the invitation of Septima Clark, where they exchanged phone numbers, philosophies, and their favorite tips about how to run a demonstration.

Two weeks later, some 300 students and observers, three times the number Baker expected, gathered at Shaw on Friday April 15. 120 black student activists representing 56 colleges and high schools in twelve southern states and the District of Columbia attended, along with observers from thirteen student and social reform organizations, representatives from northern and border state colleges, and a dozen southern white students.

One of the largest delegations at the Raleigh conference, and the one that would subsequently provide SNCC with a major share of its leaders, was the Nashville student group. Fisk University provided a number of these protest leaders, most notably Marion Barry and Diane Nash. Another Nashville protest leader, John Lewis, was a ministerial student at American Baptist Theological Seminary.

King spoke to the press and students at the beginning of the meeting, emphasizing “the need for some type of continuing organization.” He hoped that the students would weigh a nationwide selective buying campaign, and that they also “seriously consider training a group of volunteers who will willingly go to jail rather than pay bail or fines.

That evening James Lawson delivered a keynote speech on the importance of nonviolence. Lawson expressed a visionary set of ideas that distinguished the student activists both from the rest of society and from more moderate civil rights leaders. On Saturday, the delegates split up into discussion groups to talk about nonviolent protest and the next steps for the student movement. When the delegates assembled on Saturday afternoon, King spoke to them, praising Lawson’s speech.

The student delegates held the final plenary meeting on Sunday. A “temporary” Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was approved, to be headquartered in Atlanta, with King and Lawson each serving as advisors. The only controversy was over whether only southern students, and not northern ones, would be represented on that committee. A compromise solution was agreed upon, and the delegates departed from what almost all agreed had been an encouraging conference.

Lawson’s influence was evident in the conference’s general emphasis on nonviolence.

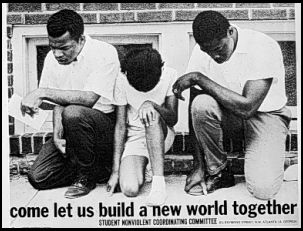

Students at the conference affirmed their commitment to the nonviolent doctrines popularized by King, yet they were drawn to these ideas not because of King’s advocacy but because they provided an appropriate rationale for student protest. SNCC’s founding was an important step in the transformation of a limited student movement to desegregate lunch counters into a broad and sustained movement to achieve major social reforms.

Ms. Baker’s speech to the conference, entitled “More than a Hamburger”, warned that work was just beginning: integrating lunch counters was one thing, breaking down barriers in areas as racially and culturally entrenched as voting rights, education and the workplace was going to be much tougher. Ms. Baker also warned: don’t let anyone else, especially the older folks, tell you what to do. A few months later Ella Baker wrote in The Southern Patriot that the student conference made it “crystal clear that the current sit-in and other demonstrations are concerned with something bigger than a hamburger…The Negro and white students, North and South, are seeking to rid America of the scourge of racial segregation and discrimination—not only at the lunch counters but in every aspect of life.”

At the Raleigh conference Guy Carawan sang a new version of “We Shall Overcome,” which had previously been adapted from a religious hymn, “I’ll be Alright” into an old labor song. This new song would become the national anthem of the civil rights movement. People joined hands and gently swayed in time singing “Deep in my heart, I do believe, we shall overcome some day.” This bonding act of camaraderie represented a coming together and reaching out to one another for strength and spiritual support.

The conference ratified a Statement of Purpose drafted by Lawson (reproduced below). Marion Barry, SNCC’s newly elected chairman, conducted his first press conference for the few reporters covering the meeting. (Barry resigned the chair of SNCC in the fall to return to graduate work at Fisk University; Charles McDew then became SNCC’s second chair).

The student movement’s temporary coordinating committee held its first official meeting in Atlanta on May 13 and 14. The 11 students present ratified the statement of purpose and voted to hire a temporary staff member whom SCLC offered to house in its office at 208 Auburn Avenue, Atlanta. Baker recruited Jane Stembridge, daughter of a white Baptist minister from Virginia and a student at Union Theological Seminary, to run the SNCC office until a permanent administrative secretary could be found. In June, Stembridge and other student volunteers published the first issue of SNCC’s newspaper, the Student Voice.

In July, Baker and Stembridge were joined by Robert Moses, a former graduate student at Harvard Univ. When Stembridge suggested that Moses assist SNCC by recruiting black leaders in the Deep South for an October conference, he agreed to do so at his own expense.

Also during that summer Barry and other SNCC representatives were given an opportunity to address members of the platform committees of each party at the Democratic and Republican conventions. Stembridge addressed the National Student Association (NSA) at its annual convention in August.

At a fall conference at Atlanta University on October 14-15, 1960, SNCC attempted to consolidate the student protest movement by establishing an organizational structure and clarifying its goals and principles. Topics covered in workshops included desegregation of public facilities, black political activity, discrimination in employment, and racial problems in education. Workshop leaders included black students who had been active in sit-ins – Diane Nash, Ben Brown of Clark College, and Charles McDew of South Carolina State College – a white southern student, Sandra Cason of the Univ. of Texas, and Timothy Jenkins from the National Student Association. About 140 delegates, alternatives and observers from 46 protest centers attended the conference, as well as over 80 observers from northern colleges and sympathetic organizations. The principal accomplishment of the conference was to create a permanent organizational structure for SNCC. The delegates voted to drop “temporary” from their name, and established a Coordinating Committee to be composed of one representative from each southern state and the District of Columbia. In addition, there was to be a staff made up of field secretaries and an expanded office staff. The going salary was $10.00 a week.

The October conference marked a turning point in the development of the student protest movement. SNCC gained permanent status, and its student leaders became increasingly confident of their ability to formulate the future course of the movement. Charles McDew, a native of Massilon, Ohio and a student at South Carolina State, replaced Barry as chairman. McDew served as chair until the election of John Lewis in 1963.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Statement of Purpose adopted in April 1960

We affirm the philosophical or religious ideal of nonviolence as the foundation of our purpose, the presupposition of our faith, and the manner of our action. Nonviolence as it grows from Judaic-Christian tradition seeks a social order of justice permeated by love. Integration of human endeavor represents the crucial first step toward such a society.

Through nonviolence, courage displaces fear; love transforms hate. Acceptance dissipates prejudice; hope ends despair. Peace dominates war; faith reconciles doubt. Mutual regard cancels enmity. Justice for all overthrows injustice. The redemptive community supersedes systems of gross social immorality.

Love is the central motif of nonviolence. Love is the force by which God binds man to Himself and man to man. Such love goes to the extreme; it remains loving and forgiving even in the midst of hostility. It matches the capacity of evil to inflict suffering with an even more enduring capacity to absorb evil, all the while persisting in love.

By appealing to conscience and standing on the moral nature of human existence, nonviolence nurtures the atmosphere in which reconciliation and justice become actual possibilities.

Sources:

BEARING THE CROSS, David J. Garrow, pp. 131 et seq.;

EYES ON THE PRIZE, Juan Williams, p. 137

IN STRUGGLE, Clayborne Carson. Ch. 2

Ijele: Art eJournal of the African World (2001): http://www.ijele.com/vol2.1/morton.html

ELLA BAKER AND THE BLACK FREEDOM MOVEMENT, Barbara Ransby, Ch. 8

WALKING WITH THE WIND: A MEMOIR OF THE MOVEMENT, John Lewis, p.115

ELLA BAKER: FREEDOM BOUND, Joanne Grant, Ch. 7

FREEDOM’S DAUGHTERS, Lynne Olson, 148-49

ORGANIZING BLACK AMERICA, Nina Mjagkij, P. 647

PARTING THE WATERS, Taylor Branch, 290